Filed under: Book Reviews, Plays | Tags: aeschylus, aristophanes, euripides, greek tragedy, literature, play, reading, the frogs

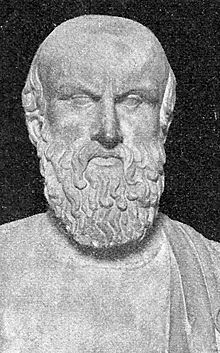

Aristophanes

Aristophanes’s The Frogs is a comedy containing, among other things, a journey, a contest, and some pointed literary and political criticism. I first heard of the play while I was studying for the literature GRE, and the synopsis was so funny that when I heard of the Classic Circuit’s Ancient Greeks tour this was the first work I thought of reading. Also, it is pretty short – it only takes about an hour to read the play.

Euripides, author of Medea, has recently died, leaving Athenian tragedy in turmoil. The god Dionysus decides to set out for the Underworld with his servant, Xanthias, to recover Euripides, because he doesn’t see much hope for tragedy among the writers who remain:

DIO. Those be mere vintage-leavings, jabberers, choirs

Of swallow-broods, degraders of their art,

Who get one chorus, and are seen no more,

The Muses’ love once gained. But O my friend,

Search where you will, you’ll never find a true

Creative genius, uttering startling things.

Dionysus seeks the advice of his half-brother, Heracles, on how best to reach Pluto’s realm; the advice he receives is a fair guide to the tone of the remainder of the play.

DIO. O drop that, can’t you? And tell me this: of all the roads you

know

Which is the quickest way to get to Hades? I want one not too warm, nor yet too cold.

HER. Which shall I tell you first? which shall it be?

There’s one by rope and bench: you launch away

And—hang yourself.

DIO. No thank you: that’s too stifling.

HER. Then there’s a track, a short and beaten cut.

By pestle and mortar.

DIO. Hemlock, do you mean?

HER. Just so.

DIO. No, that’s too deathly cold a way;

You have hardly started ere your shins get numbed.

HER. Well, would you like a steep and swift descent?

DIO. Aye, that’s the style: my walking powers are small.

HER. Go down to the Cerameicus.

DIO. And do what?

HER. Climb to the tower’s top pinnacle—

DIO. And then?

HER. Observe the torch-race started, and when all

The multitude is shouting Let them go,

Let yourself go.

DIO. Go whither?

HER. To the ground.

DIO. O that would break my brain’s two envelopes. I’ll not try that.

Euripides

Dionysus and Xanthias travel with Heracles’s lion skin, rather than taking the aforementioned advice, and when they reach the Underworld there is a lot of switching the cloak back and forth as Dionysus sees it to his advantage. That is, if someone seems pissed to see Heracles, he gives the lion skin to Xanthias.

When they at last make it through to see Pluto, they learn that the Underworld is in turmoil. The recently dead Euripides is trying to claim Aeschylus’s seat at Pluto’s dinner table; only the “Best Tragic Poet” may take that seat. Dionysus is made judge of the contest between the two, and the poets begin picking at each other’s work, trying to uncover whose is the weightier and whose has the better meter.

It’s been a while since I’ve read any really, really old literature (as this could be termed), and when I started reading The Frogs I suspected this would be one of so many cases when the synopsis is far funnier than the play itself. The play, though, is funny and totally worth reading in that there are so many bits of wordplay and humor that can’t come across in the sort of broad summary I give here, as when Aeschylus shows how formulaic Euripides’s prologues are by adding “… lost his little flask of oil” to each one. (The line works every time.) Or when Dionysus, unable to decide who has won the contest even after the lengthy bout of literary criticism, decides to “weigh the art poetic like a pound of cheese” and we find that it’s the actual weight of the things discussed that decides this part of the contest. (See: two crashed chariots and dead charioteers outweigh a mace.)

Aeschylus

There’s a lot of discussion throughout the play about the style and subject matter of Euripides and Aeschylus. Euripides wrote about “real” people with faults, while Aeschylus wrote about heroes and gods, people the audience could emulate. Which is better, and more vital to recovering the state of Athenian tragedy?

Probably the most fun thing about reading this play was discovering how accessible it is. I may only have the vaguest idea of who Euripides and Aeschylus were (mostly garnered from Wikipedia), but I was still able to understand much of the play as it related to criticism of the writers’ dramas. The political implications of Aristophanes’s comedy, not so much; but that’s something for another day.

Read The Frogs at Project Gutenberg